How Would Jesus Talk if He Were a Politician?

Jesus’ commandment to be “in the world but not of the world” is never more needed than at election time. But nowhere do we find it more difficult. Our scriptures tell us that “such as will administer the law in equity and justice should be sought for.” (D&C 134:3.) But too often those promoting candidates at both ends of the political spectrum speak of their opponents with language that falls far short of the standard of “virtuous, lovely, of good report, or praiseworthy” that Latter-day Saints profess to seek.

Partisans seldom limit their words to analyzing the merits of their opponents’ policies. More often they resort to personal attacks, name calling, and ridicule. They freely distort an opponent’s record and his words. They impugn his motives and his integrity. Rather than give him the benefit of the doubt, they cast him in the worst possible light. Occasionally, politicians and their supporters have even resorted to physical violence.

What Would Jesus Do?

It may be worth asking what Jesus would do. Peter reminded his readers that “Christ also suffered for us, leaving us an example, that ye should follow his steps.” (1 Peter 2:21.) And Jesus, answering His own question to the Nephites as to “what manner of men ought ye to be?” said, “Verily I say unto you, even as I am.” (3 Nephi 27:27.)

Jesus, of course, never ran for office. He taught that His kingdom was not of this world. But He did leave teachings which may help us answer how He would have acted if He had in fact been a candidate. And His modern prophets have given additional counsel and examples that we may find useful.

First and foremost, Jesus taught that “By this shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another.” (John 13:35.) He added: “All things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.” (Matthew 7:12.)

The Savior exemplified His own teachings. He was a friend to those most despised by the religious leaders of His day. He didn’t approve the actions of publicans and harlots, but He condemned the sin, not the sinner. When the pharisees wanted to stone a woman taken in adultery, Jesus simply sent her on her way with the counsel to sin no more. He spent time with Samaritans who faced discrimination from other Jews. While He hung on the cross, He prayed, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

As the pre-mortal Jehovah, the Lord had taught the same principle to ancient Israel. In Exodus 22:28 he admonished: “Thou shalt not … curse the ruler of thy people.” The writer of Ecclesiastes took it a step further: “Curse not the king, no not in thy thought.” (Eccl. 10:20.)

Jesus’ early apostles took the same approach. Peter lamented that there were those in his day who “despise[d] government” and were so presumptuous they were “not afraid to speak evil of dignities.” (2 Peter 2:10.) Paul also felt a divine obligation to speak respectfully of earthly leaders, whether religious or political. When the high priest Ananias commanded that he be struck on the mouth, Paul unleashed some heartfelt invective. But when informed that he was speaking to the high priest, he apologized. He explained that he hadn’t realized that Ananias was the high priest. He quoted applicable scripture: “It is written, Thou shalt not speak evil of the ruler of thy people.” (Acts 23:5.) Paul wasn’t any happier with the actions of Ananias than he had been when he didn’t know who he was. But he did recognize the need to show respect for the office and not to speak ill of the office holder.

It is clear that the Lord has commanded His children to speak well of those with whom they may disagree. But why? Wouldn’t He want us to energetically promote good causes and attempt to eradicate evil? Of course. But only in His way. As He reminded Isaiah, “My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways.” (Isaiah 55:8.)

There are three major reasons for not resorting to negative campaigning and personal insults. First, it is often counterproductive. Secondly, it is contagious and promotes similar incivility in others, poisoning the entire body politic. Finally, it causes serious spiritual harm to the one who engages in it. Let’s examine each of those points in more detail.

Incivility is less effective

Conservative activist Jim Fossel wrote:

Your political opponents being mean and nasty toward you doesn’t mean you ought to respond in kind…. In doing so, you not only (however inadvertently) acknowledge their attacks as legitimate, but also lower yourself to their level. That makes it harder for those who might otherwise sympathize with you to rally to your side as a victim; the conflict often ends up being perceived as a wash, no matter which side started it or was more negative.

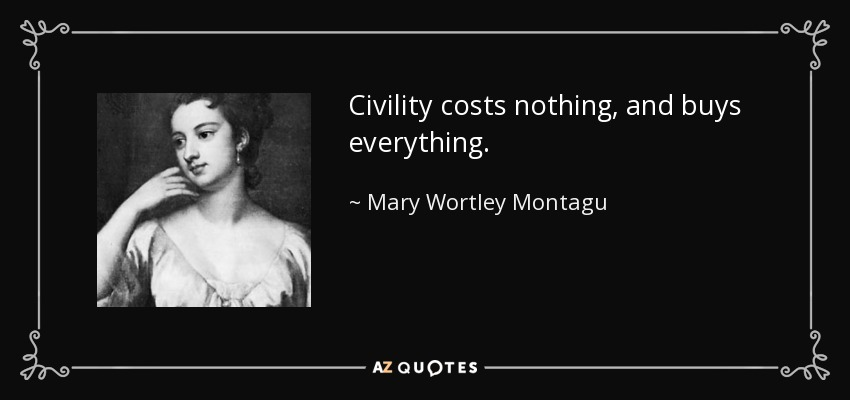

Jeremy Frimer at the University of Winnipeg and Linda Skitka at the University of Illinois at Chicago recently reported a study which shows that Americans overwhelmingly are offended by name calling and inflammatory political rhetoric, no matter what its source. They found that the nastier a politician’s language was, the lower the public’s approval of him. When he showed respect and restraint, his ratings rose. This was true even among the politician’s own supporters.

Frimer and Skitka also analyzed transcripts of congressional debates between 1990 and 2015 and studied the public’s approval of Congress during that same time. They found that the less civil the debates, the lower the public’s approval of Congress in general.

English author and poet Lady Mary Wortley Montagu observed, “Civility costs nothing and buys everything.” Those with a stake in the upcoming elections would do well to take note.

Incivility is contagious and harmful to society

Secondly, when one resorts to personal attacks and angry ridicule, he invites a response in kind from the other side. By his example, he also encourages those of the same political persuasion to speak the same way. President Dallin H. Oaks, former chief justice of the Utah Supreme Court and current first counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints commented:

If representative government is to function effectively under our constitutions, we must have civility in political discourse. We currently have an excess of ugliness and contentiousness in our communications on many political issues. I don’t need to give examples; we have all been exposed to it, and some of us have occasionally been part of it. We all bear some responsibility for the current political polarization and the stalemates that have resulted from it. We ought to tone it down. Meaningful debate and discussion about policies, programs, and procedures is essential to a democratic society. But contentiousness for the sake of division is bad for democracy. It is bad for law observance. It is bad for neighborly relations. And it is particularly destructive as an example for the rising generation, who, if not taught better, will perpetuate and magnify its ugliness and divisiveness for generations to come. (Dallin H. Oaks, Sept. 17, 2010: Maintain Civility in Political Discourse.)

The contagious nature of incivility at its worst is shown by the effects of King Noah’s reign as described in the Book of Mormon. A reasonably upright community changed almost 180 degrees in short order once their first leader, Zeniff, died and his son took over the reins. The record tells us:

Behold, he did not keep the commandments of God, but he did walk after the desires of his own heart…. And he did cause his people to commit sin, and do that which was abominable in the sight of the Lord. Yea, and they did commit whoredoms and all manner of wickedness…. And they also became idolatrous, because they were deceived by the vain and flattering words of the king and priests; for they did speak flattering things unto them.” (Mosiah 11:2, 7.)

A more modern example of the effect one leader can have on a nation is that of Adolph Hitler. As reviled as he is today, some have recognized him as the most popular leader in history within the borders of his own country.

Incivility does greatest harm to the incivil

The third and perhaps greatest reason the Lord has counseled His children to speak well of others is the effect it has on the speaker himself. The Lord warns in the Book of Mormon that “the spirit of contention is not of me, but is of the devil, who is the father of contention, and he stirreth up the hearts of men to contend with anger, one with another.” (3 Nephi 11:29).

One of the scriptural titles of Satan is “the accuser of our brethren.” (Rev. 12:10.) That may help us understand why we are told in D&C 50:33 that we are not to use “railing accusation” even against the devil, lest we be seized with the same diabolical spirit. When we speak unkindly of another, no matter how justified we may think the criticism is, we alienate ourselves from the Spirit of the Lord. That Spirit is a spirit of love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, [and] temperance.” (Galatians 5:22-23.) It is quite incompatible with a spirit of hatred, impatience, strife, pride, and accusation, which is so often found on the campaign trail and which is the mark of a Satanic spirit, regardless of the merits of the cause or candidate one is supposedly supporting.

The example of modern prophets

Latter-day Saint prophets have not only taught but exemplified the importance of being able to disagree without being disagreeable. Both President Gordon B. Hinckley and President Thomas S. Monson received elaborate praise from local clergy when they died. Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, and Muslim leaders were unanimous in lauding both men for their kindness and efforts to work together with them on projects of common interest.

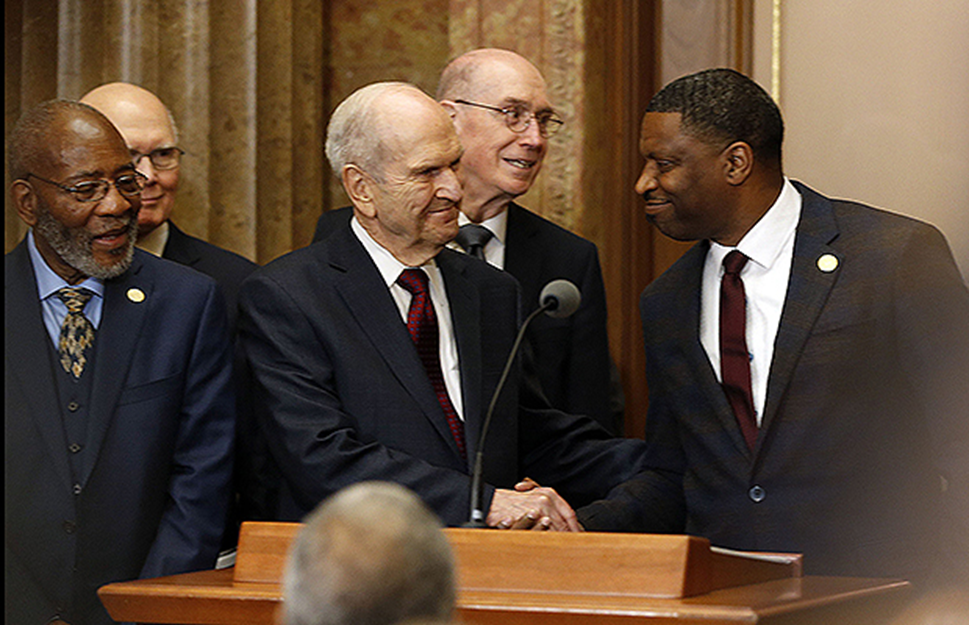

Church presidents have been similarly cordial and respectful to US presidents and other leaders from both political parties. While they may have had very different points of view on various issues, they did not let that keep them from treating the presidents themselves with warmth and courtesy. The following photos are illustrative of such relationships:

So how do we proceed?

How can we energetically and effectively support candidates and measures we feel strongly about without speaking and acting in ways that will offend the Spirit of the Lord?

- We can speak respectfully of the other person, beginning with how we refer to him. Josiah Quincy, in his book Figures of the Past, tells of a conversation between Joseph Smith and a Methodist minister. The minister suddenly exclaimed, “Why I told my congregation the other Sunday that they might as well believe Joe Smith as such theology as that.”

“Did you say Joe Smith in a sermon?” inquired the Prophet.

“Of course I did. Why not?”

Quincy reported that the “reply was given with a quiet superiority that was overwhelming”: “Considering only the day and the place, it would have been more respectful to have said Lieutenant-General Joseph Smith.”

When we derisively refer to a president or other leader only by his last name (or worse, only by his first name), we do him no harm. But we diminish ourselves and prove to our listeners that we are of less character than the object of our derision.

- We can and should emphasize the virtues of the candidates of our choice and attempt to persuade others of their superiority. We can argue the merits of policies we favor and the pitfalls of proposals with which we disagree.

- We can give those with whom we disagree the benefit of the doubt. We can presume they are acting in good faith and simply see things differently or honestly have different priorities from our own.

- We can banish name-calling, mockery, and personal attacks from our repertoire.

I’m convinced we will do more to advance the causes in which we believe by emphasizing the positive of our own candidates and their policies than by attacking those on the other side. But even if we do not prevail, we will have maintained our integrity. We will have complied with the Lord’s commandments. And we will qualify ourselves for the continued companionship of the Holy Spirit, with the peace, love, and joy which it brings.

Appendix: Selected statements on the subject of civility

Proverbs 13:10: Only by pride cometh contention.

JST, Matthew 7:2: Judge not unrighteously, that ye be not judged; but judge righteous judgment. (Joseph Smith Translation.)

D&C 19:30: And thou shalt do it with all humility, trusting in me, reviling not against revilers.

D&C 134:6: We believe that every man should be honored in his station, rulers and magistrates as such, being placed for the protection of the innocent and the punishment of the guilty; and that to the laws all men owe respect and deference, as without them peace and harmony would be supplanted by anarchy and terror; human laws being instituted for the express purpose of regulating our interests as individuals and nations, between man and man; and divine laws given of heaven, prescribing rules on spiritual concerns, for faith and worship, both to be answered by man to his Maker. (D&C 134:6)

John Adams:

We may please ourselves with the prospect of free and popular governments, God grant us the way. But I fear that in every assembly, members will obtain an influence by noise rather than sense, by meanness rather than greatness, and by ignorance and not learning. There is one thing…that must be attempted and most sacredly observed, or we are all undone. There must be decency and respect and Civil Discourse veneration introduced for persons of every rank, or we are undone. In popular government, this is our only way.

Ezra Taft Benson, Beware of Pride, April 1989 General Conference:

In the premortal council, it was pride that felled Lucifer, “a son of the morning.” (2 Ne. 24:12–15; see also D&C 76:25–27; Moses 4:3.) At the end of this world, when God cleanses the earth by fire, the proud will be burned as stubble and the meek shall inherit the earth. (See 3 Ne. 12:5, 3 Ne. 25:1; D&C 29:9; JS—H 1:37; Mal. 4:1.) ….

The central feature of pride is enmity—enmity toward God and enmity toward our fellowmen. Enmity means “hatred toward, hostility to, or a state of opposition.” It is the power by which Satan wishes to reign over us. …

Another major portion of this very prevalent sin of pride is enmity toward our fellowmen. We are tempted daily to elevate ourselves above others and diminish them. (See Hel. 6:17; D&C 58:41.)

The proud make every man their adversary by pitting their intellects, opinions, works, wealth, talents, or any other worldly measuring device against others. In the words of C. S. Lewis: “Pride gets no pleasure out of having something, only out of having more of it than the next man. … It is the comparison that makes you proud: the pleasure of being above the rest. Once the element of competition has gone, pride has gone.” (Mere Christianity, New York: Macmillan, 1952, pp. 109–10.)….

The scriptures abound with evidences of the severe consequences of the sin of pride to individuals, groups, cities, and nations. “Pride goeth before destruction.” (Prov. 16:18.) It destroyed the Nephite nation and the city of Sodom. (See Moro. 8:27; Ezek. 16:49–50.) ….

When pride has a hold on our hearts, we lose our independence of the world and deliver our freedoms to the bondage of men’s judgment. The world shouts louder than the whisperings of the Holy Ghost. The reasoning of men overrides the revelations of God, and the proud let go of the iron rod. (See 1 Ne. 8:19–28; 1 Ne. 11:25; 1 Ne. 15:23–24.)

Pride is a sin that can readily be seen in others but is rarely admitted in ourselves. Most of us consider pride to be a sin of those on the top, such as the rich and the learned, looking down at the rest of us. (See 2 Ne. 9:42.) There is, however, a far more common ailment among us—and that is pride from the bottom looking up. It is manifest in so many ways, such as faultfinding, gossiping, backbiting, murmuring, living beyond our means, envying, coveting, withholding gratitude and praise that might lift another, and being unforgiving and jealous….

Selfishness is one of the more common faces of pride. “How everything affects me” is the center of all that matters—self-conceit, self-pity, worldly self-fulfillment, self-gratification, and self-seeking.

Pride results in secret combinations which are built up to get power, gain, and glory of the world. (See Hel. 7:5; Ether 8:9, 16, 22–23; Moses 5:31.) This fruit of the sin of pride, namely secret combinations, brought down both the Jaredite and the Nephite civilizations and has been and will yet be the cause of the fall of many nations. (See Ether 8:18–25.)

Another face of pride is contention. Arguments, fights, unrighteous dominion, generation gaps, divorces, spouse abuse, riots, and disturbances all fall into this category of pride.

Contention in our families drives the Spirit of the Lord away. It also drives many of our family members away. Contention ranges from a hostile spoken word to worldwide conflicts. The scriptures tell us that “only by pride cometh contention.” (Prov. 13:10; see also Prov. 28:25.)

The scriptures testify that the proud are easily offended and hold grudges. (See 1 Ne. 16:1–3.) They withhold forgiveness to keep another in their debt and to justify their injured feelings….

Pride is a damning sin in the true sense of that word. It limits or stops progression. (See Alma 12:10–11.) The proud are not easily taught. (See 1 Ne. 15:3, 7–11.) They won’t change their minds to accept truths, because to do so implies they have been wrong.

Pride adversely affects all our relationships—our relationship with God and His servants, between husband and wife, parent and child, employer and employee, teacher and student, and all mankind. Our degree of pride determines how we treat our God and our brothers and sisters. Christ wants to lift us to where He is. Do we desire to do the same for others?

Pride fades our feelings of sonship to God and brotherhood to man. It separates and divides us by “ranks,” according to our “riches” and our “chances for learning.” (3 Ne. 6:12.) Unity is impossible for a proud people, and unless we are one we are not the Lord’s. (See Mosiah 18:21; D&C 38:27; D&C 105:2–4; Moses 7:18.) ….

Pride is the universal sin, the great vice. Yes, pride is the universal sin, the great vice….

God will have a humble people. Either we can choose to be humble or we can be compelled to be humble. Alma said, “Blessed are they who humble themselves without being compelled to be humble.” (Alma 32:16.)

Let us choose to be humble.

Dallin H. Oaks, Oct 2014 conference:

On the subject of public discourse, we should all follow the gospel teachings to love our neighbor and avoid contention. Followers of Christ should be examples of civility. We should love all people, be good listeners, and show concern for their sincere beliefs. Though we may disagree, we should not be disagreeable. Our stands and communications on controversial topics should not be contentious. We should be wise in explaining and pursuing our positions and in exercising our influence. In doing so, we ask that others not be offended by our sincere religious beliefs and the free exercise of our religion. We encourage all of us to practice the Savior’s Golden Rule: “Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them” (Matthew 7:12).

The Mormon Ethic of Civility, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Newsroom, 16 October 2009:

The political world is astir. Economies are faltering. Public trust is waning. Individuals feel vulnerable. And social cohesion wears thin. Meanwhile, stories of rage and agitation fill our airwaves, streets and town halls. Where are the voices of balance and moderation in these extreme times? During a recent address given in an interfaith setting, Church President Thomas S. Monson declared: “When a spirit of goodwill prompts our thinking and when united effort goes to work on a common problem, the results can be most gratifying.” Further, former Church President Gordon B. Hinckley once said that living “together in communities with respect and concern one for another” is “the hallmark of civilization.” That hallmark is under increasing threat. So many of the habits and conventions of modern culture — ubiquitous media, anonymous and unsourced online participation, politicization of the routine, fractured community and family life — undermine the virtues and manners that make peaceful coexistence in a pluralist society possible. The fabric of civil society tears when stretched thin by its extremities. Civility, then, becomes the measure of our collective and individual character as citizens of a democracy. A healthy democracy maintains equilibrium through diverse means, including a patchwork of competing interests and an effective system of governmental checks. Nevertheless, this order ultimately relies on the integrity of the people. Speaking at general conference, a semiannual worldwide gathering of the Church, Elder D. Todd Christofferson of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles asserted: “In the end, it is only an internal moral compass in each individual that can effectively deal with the root causes as well as the symptoms of societal decay.” Likewise, Presiding Bishop H. David Burton emphasized that the virtues of fidelity, charity, generosity, humility and responsibility “form the foundation of a Christian life and are the outward manifestation of the inner man.” Thus, moral virtues blend into civic virtues. The seriousness of our common challenges calls for an equally serious engagement with reasonable ideas and solutions. What we need is rigorous debate, not rancorous altercations. Civility is not only a matter of discourse. It is primarily a mode of engagement. The technological interconnectedness of society has made isolation impossible. Of all the institutions in the modern world, religion has had perhaps the greatest difficulty adjusting to the reality of give and take with the public. Today, and throughout its history, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints continuously encounters the legitimate interests of various stakeholders in its interaction with the public. Rather than exempting itself from the rules of law and civility, the Church has sought the path of cooperative engagement and avoided the perils of acrimonious confrontation. Echoing this mode of civil engagement, President Monson declared: “As a church we reach out not only to our own people but also to those people of goodwill throughout the world in that spirit of brotherhood which comes from the Lord Jesus Christ.” Speaking of civility on a personal level, Elder Robert D. Hales of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles taught Latter-day Saints how to respond to criticism: “Some people mistakenly think responses such as silence, meekness, forgiveness, and bearing humble testimony are passive or weak. But, to ‘love [our] enemies, bless them that curse [us], do good to them that hate [us], and pray for them which despitefully use [us], and persecute [us]’ (Matthew 5:44) takes faith, strength, and, most of all, Christian courage.”

The moral basis of civility is the Golden Rule, taught by a broad range of cultures and individuals, perhaps most popularly by Jesus Christ: “And as ye would that men should do to you, do ye also to them likewise” (Luke 6:31). This ethic of reciprocity reminds us all of our responsibility toward one another and reinforces the communal nature of human life. Similarly, the Book of Mormon tells a sober story of civilizational decline in which various peoples repeat the cycle of prosperity, pride and fall. In almost every case, the seeds of decay begin with the violation of the simple rules of civility. Cooperation, humility and empathy gradually give way to contention, strife and malice. The need for civility is perhaps most relevant in the realm of partisan politics. As the Church operates in countries around the world, it embraces the richness of pluralism. Thus, the political diversity of Latter-day Saints spans the ideological spectrum. Individual members are free to choose their own political philosophy and affiliation. Moreover, the Church itself is not aligned with any particular political ideology or movement. It defies category. Its moral values may be expressed in a number of parties and ideologies. Furthermore, the Church views with concern the politics of fear and rhetorical extremism that render civil discussion impossible. As the Church begins to rise in prominence and its members achieve a higher public profile, a diversity of voices and opinions naturally follows. Some may even mistake these voices as being authoritative or representative of the Church. However, individual members think and speak for themselves. Only the First Presidency and the Twelve Apostles speak for the whole Church. Latter-day Saint ethical life requires members to treat their neighbors with respect, regardless of the situation. Behavior in a religious setting should be consistent with behavior in a secular setting. The Church hopes that our democratic system will facilitate kinder and more reasoned exchanges among fellow Americans than we are now seeing. In his inaugural press conference President Monson emphasized the importance of cooperation in civic endeavors: “We have a responsibility to be active in the communities where we live, all Latterday Saints, and to work cooperatively with other churches and organizations. My objective there is … that we eliminate the weakness of one standing alone and substitute for it the strength of people working together.”

Political Neutrality, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Newsroom:

The Church does:

- Encourage its members to play a role as responsible citizens in their communities, including becoming informed about issues and voting in elections.

- Expect its members to engage in the political process in an informed and civil manner, respecting the fact that members of the Church come from a variety of backgrounds and experiences and may have differences of opinion in partisan political matters.

Civility, Beliefs and America’s Toxic Political Scene, by Peter Orvetti, Posted by Guest Voice, Apr 7th, 2010

You don’t have to give up your beliefs to respect those with different ones.

There is a common misconception in our increasingly toxic political environment that only pragmatists and compromisers can find ways to be civil. How, this argument goes, can those with decidedly conflicting views on stark matters like abortion, gay equality, terrorism, or foreign intervention ever really get along? Is “considerate” just a nicer way of saying “milquetoast”?

Sen. Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, one of the most visible conservative ideologues on Capitol Hill, disproved this sentiment during a trip back home. Appearing at a town hall meeting, Coburn defended House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, saying, “I’m 180 degrees in opposition to the speaker — she’s a nice lady.” When the crowd grumbled, he continued, “How many of you all have met her? … Just because somebody disagrees with you doesn’t mean they’re not a good person.”

Coburn also got to the heart of the trend toward political polarization by pointing out the perils of getting news just from one source, or from one perspective. He urged the crowd to not “just watch Fox News or CNN — watch ‘em both.” In a time when those on the left click over to Daily Kos and Keith Olbermann while those on the right have their Hannity and Limbaugh and Little Green Footballs, Coburn said he reads the liberal New York Times and Washington Post as well as the conservative Wall Street Journal to “get a perspective” and “know what other people’s thoughts are — not just what I hear through a pipe channel.”

Coburn, who entered the Senate with Barack Obama and became one of the future president’s closest friends in the chamber, is not the first ideologue to put civility ahead of rancor. Orrin Hatch and Ted Kennedy were very close, despite the differences in both their beliefs and their lifestyles. (In fact, it was the latter that helped bring them together – Hatch, a Mormon teetotaler, helped Kennedy as he struggled with ending his dependence on alcohol.) The tradition goes back to the Republic’s earliest days, when John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were first allies, then bitter rivals, then intimate friends.

Kathleen Parker, a conservative syndicated columnist, became a chief voice for civility after an unsettling experience in 2008. Parker wrote a fair and dispassionate column in September of that year, urging Sarah Palin to leave the Republican national ticket for the good of the party. A shaken Parker reported in her subsequent column that readers had written to call her a “traitor” and to say her mother “should have aborted me and left me in a dumpster.” Parker said that after two decades as a pundit, she was used to angry mail, but that these missives were “not just angry, but vicious and threatening.”

Parker later used her national platform to promote the Johns Hopkins Civility Project, founded in 1997 by P.M. Forni, as well as Mark DeMoss’s Civility Project, which “urges a voluntary pledge to be civil in discourse and behavior and to stand against incivility.” Like Coburn, Parker sees modern media as part of the problem. She wrote that while “in previous eras, an uncivil exchange might be confined to a room, a building or a public square, today’s media technology means that it is captured, amplified, replayed and distributed — perpetually.”

Making wild accusations against those in power, and tossing crazed slurs their way, is an American tradition. But in the age of cable television and the Internet, the tradition has grown uglier. Bill Clinton was accused of drug-running; George W. Bush was accused of planning and profiting off of 9/11. Bush was booed by Democrats during his 2005 State of the Union address – not over the emotional issue of the war in Iraq, but over his plans to reform the government pension system.

This sort of thing is cleverly stoked by the professional agitators of both left and right. Ann Coulter, a supporter of “sending liberals to Guantanamo,” once said, “My only regret with Timothy McVeigh is he did not go to the New York Times building.” On the other side, Michael Moore called Bush “a deserter, an election thief, a drunk driver, a WMD liar, and a functional illiterate.”

Progressive columnist Molly Ivins, a veteran Bush critic, wrote of her bête noire that “he is by and large perfectly affable. You would have to work at it to dislike him personally.” Ivins sardonically added, “Did you know that it is quite possible not to hate someone and at the same time notice their policies are disastrous for people in this country? Quite a thought, isn’t it? Grown-ups can actually do that – can think a policy is disastrous without hating the person behind it.”

For many angry Americans on all sides, the political has become far too personal.et

Don’t expect civility, by Mark DeMoss, in Politico, January 17, 2011:

A nation that debates tax policy or foreign policy is now focusing on civility. The terrible Jan. 8 shooting spree in Tucson has added new fuel to the fire of both liberals and conservatives.

The debate over which political side is most uncivil has dwarfed our nation’s crucial discussion of public safety, mental illness and the right to bear arms. I pray that six people, including a sweet young girl, did not die so we could stage a playground fight over which side threw the first stone or said the meanest things.

President Barack Obama, in his Tucson speech on Wednesday, talked about our need to be more civil. “If this tragedy prompts reflection and debate—as it should,” Obama said, “let’s make sure it’s worthy of those we have lost. Let’s make sure it’s not on the usual plane of politics and point-scoring and pettiness.” Obama expressed the hope that “their death helps usher in more civility in our public discourse.”

Yet, there seems little chance of change unless more political leaders begin sounding the same clarion call. Which looks unlikely. Sadly, every member of Congress – except three — and every governor declined to sign a civility pledge I mailed out last May.

The bar couldn’t have been lower. Here is what they were asked to sign: I will be civil in my public discourse and behavior; I will be respectful of others whether or not I agree with them; and I will stand against incivility when I see it.

I launched The Civility Project on the eve of Obama’s inauguration. Since I am a conservative Republican and evangelical, I asked Lanny Davis, a liberal Democrat and a Jew, to work with me. I didn’t want to lecture the left on incivility, for there’s plenty of that on the right.

Given how low we set the bar, we expected many leaders to sign. But we were dreaming. Despite a recent poll revealing that 83 percent of Americans say, “People should not vote for candidates and politicians who are uncivil,” only Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.), Rep. Frank Wolf (R-Va.) and Rep. Sue Myrick (R-N.C.) signed the pledge.

So, after two years, I have decided to dissolve it. I told the three signers in a Jan. 3 letter. Though the Tucson tragedy and current political debate prompted me to reconsider, I’m now hopeful that a growing chorus calling for a more civil nation will be heard.

I haven’t lost my passion for increased civility. I’m just not going to continue operating a project deserving more time and resources. I’ve thought long and hard about the lack of interest among our leaders. I can only conclude: too many people equate civility in public life with unilateral disarmament. Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly summed this up on his show. “I wouldn’t sign it if I were in Congress,” he told Davis, “I’d be afraid that if my opponent attacked me I wouldn’t be able to attack him back.” Most of the email from Republicans about this has complained that the Democrats started the incivility — and are meaner. Like this, from a self-identified “Real Republican: “Grow up boys and girls. The left started slinging this mud and you should give as good as you get.” He went on to call House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) , Sen. Harry Reid (D-Nev.) and Obama “communists.” There is some hope: Thousands signed this pledge. I’ve received hundreds of emails from the left and the right, thanking us for speaking out and urging us to continue. I have also been encouraged by the words and disposition of our president—a man I did not vote for and disagree with on almost every policy issue. Still, I would defend him as a man I believe loves his family and his country and wakes up each day desiring to do what he believes is best for both. In fact, his pending 2008 election was one factor that prompted me to form this civility project. Obama has been consistent in calling for a more civil tone. Wednesday he again tried to bring the temperature down on both sides. “But at a time when our discourse has become so sharply polarized,” the consoler in chief said, “at a time when we are far too eager to lay blame for all that ails the world at the feet of those who think differently that we do—it’s important for us to pause for a moment and make sure that we are talking with each other in a way that heals, not a way that wounds.” If you don’t like Obama’s words, try these, taken from the greatest textbook of wisdom and civility ever written—the Bible. “But with humility of mind let each of you regard one another as more important than himself (Philippians 2:3).” That verse alone, if taken to heart, would make America unrecognizable — and beautiful.

Crossing the divide: President Hinckley’s words, example spurred interfaith efforts, by Elaine Jarvik, Published: February 2, 2008

For a while now, John Kesler has been carrying a little piece of paper in his wallet, in the plastic sleeve that holds his credit cards, right on top so it’s the first thing he sees. It’s a short reminder from LDS Church President Gordon B. Hinckley, urging compassion and respect, not just Mormon-to-Mormon, but Mormon to everyone else.

The church’s prophet, who died earlier this week, is being remembered for his many calls for inclusiveness, a public reaching out unprecedented in a church that was historically known for its isolation and that is often criticized for its claim to be “the only true church” — a declaration that Utahns of other faiths, in particular, often react to personally.

President Hinckley’s messages — to put friendship over proselytizing, to reach out with love and helpfulness — put Latter-day Saints on notice that he expected something better than what existed when he became president in 1995. His reminders coincided, at the turn of the last millennium, with Utah’s preparations to host the world during the 2002 Olympic Winter Games. The prospect of that global visit, with its scrutiny of Utah by the world’s media, made residents take a closer look at one of their most distinctive characteristics — a chasm most easily symbolized by the delineation of “Mormons and non-Mormons.”

President Hinckley didn’t invent inclusiveness and was by no means the only prominent Utahn to encourage it. But he is credited with making it a priority for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and with helping Mormons understand that they have a Christian duty beyond their own inner circle.

He didn’t mince words.

In an address during the church’s general conference in April 2000, he specifically instructed members to “reach out to others not of our faith. Let us never act in a spirit of arrogance or with a holier-than-thou attitude. Rather, may we show love and respect and helpfulness toward them.”

But that wasn’t all. He added a mild chastisement that cut directly to the heart of what critics and observers alike had long said: “We are greatly misunderstood, and I fear that much of it is of our own making. We can be more tolerant, more neighborly, more friendly, more of an example than we have been in the past. Let us teach our children to treat others with friendship, respect, love and admiration. That will yield a far better result than will an attitude of egotism and arrogance.”

As a majority in Utah, many Latter-day Saints had become tone deaf to the protests and needs of minority groups — whether political, ethnic or religious. So this was a wake-up call that perhaps no other Utahn could issue without being dismissed as irrelevant. And he sounded it consistently during his time as church president.

With both dissension and hope in the air, the turn of the millennium saw the emergence of several efforts to build bridges, including the Interfaith Roundtable, made up of members of many local faiths; the Alliance for Unity, to bring together not just religious faiths, but Utah’s power brokers; and Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson’s “Bridging the Religious Divide” community meetings in 2005.

Elaine Emmi has lived in the Salt Lake valley for 25 years. She’s a Quaker and the chair of the Interfaith Roundtable — and, she says, “I’m one of those weird non-Mormons that actually listen to conference.” That would be the biannual LDS general conference, which is televised but mostly draws an LDS audience.

When Emmi first heard President Hinckley speak about inclusiveness, she heard it as a message of love. She also imagined that it was a relief to Mormons: that they could just be friends with their neighbors and co-workers without having to figure out how to get them to convert.

In the many Interfaith Roundtable meetings she has attended — meetings that include clergy of many Salt Lake Valley faiths, including LDS — she says, “I have never felt I would be loved better if I were LDS.”

The current push to come together is not about a specific goal like the 1980s fight against the MX missile or the 2002 Olympics, notes Emmi , but is ongoing and broad.

Roger Keller, a former Presbyterian minister and a religion professor at Brigham Young University, says he’s seen a dramatic change in attitude and interfaith cooperation. Before serving as an early member of the Interfaith Roundtable, he approached President Hinckley and other LDS leaders as a Protestant with concerns about the way Latter-day Saints were portrayed in a film called, “The Godmakers.”

“He was very appreciative that someone from another faith tradition would be concerned about being sure things were appropriately stated about any other faith. That’s what I’ve seen in him — that desire. Even if we disagree with someone, we need to do it in a way that doesn’t disrespect or undercut.”

President Hinckley’s urging for understanding and love for those of other faiths “made my work a whole lot easier” teaching a world religions class at BYU. “It led to an openness to other faith traditions we didn’t have before,” he says.

Keller saw a dramatic shift when Utah hosted the Olympics, and the efforts of many over time to create some harmony came to fruition. President Hinckley “was not necessarily the catalyst, but by his permission he changed the climate.”

When he first started teaching at BYU, Keller quickly learned that with various faculty and many students, there was “always kind of a little chip on their shoulder about other faith traditions. They were always a little needley in what they had to say.”

What he termed “that bastion mentality” has “diminished considerably” during the past decade. “I have a feeling that his stamp is on the Quorum of the Twelve and the next prophet. President (Thomas S.) Monson has certainly done his share in that realm. We won’t see a change — if anything it will accelerate.”

It’s clear that the LDS Church’s Office of Public Affairs is committed to the dialogues that take place at the Interfaith Roundtable and a similar group called the Lunch Bunch, says the Rev. Steve Goodier, pastor of Christ United Methodist Church. The Rev. Goodier also points to the LDS Church’s standing invitation to Interfaith Roundtable members for an annual dinner and Christmas concert at the LDS Conference Center (with great seats, he says), and a $10,000 gift his church received from the LDS Foundation to help remodel Christ United Methodist.

“I find myself more heavily involved with other faith communities in Salt Lake City than I ever was in other places I’ve lived,” the Rev. Goodier says. “I believe that is directly due to the vision of tolerance of President Hinckley, and I personally appreciate that legacy he has le behind.”

President Hinckley’s call for “tolerance” among Mormons has been featured in several news clips shown in recent days. It’s a word that the Rev. Goodier says, in his faith tradition, “doesn’t mean to just abide them. In our church it means to try to understand and accept.”

But the word disheartened Elise Lazar every time she saw it on the TV news. Tolerance is only a first step, she says, and she thinks President Hinckley meant much more than that. Tolerance, she says, is “a bare minimum of ‘OK, you’re different than I am, and I’m just going to put up with you.’ I want much more than that.” Defensiveness can be found on both sides of the religious divide in Utah, and both sides “need to hear words like acceptance, honor, appreciate, in order to be able to relax our defenses.”

Lazar, who is Jewish, has lived in Salt Lake City for 21 years and says she has “been on my bandwagon” for inclusiveness that whole time. Not long aer she moved here she gave a talk that was printed in the progressive Mormon journal “Sunstone,” and aer that she was surprised to be invited to the Beehive House to meet with several LDS Church authorities.

“They wanted to hear what I wanted to say,” she recalls.

Many years later, not long after the 2002 Olympics, Lazar helped form Woman to Woman, a group of nine — four Mormons, five not — who met once a month to have a conversation about their beliefs, their differences and their common ground.

Some of the group’s members have met several times with LDS Church authorities, including Elder Merrill Bateman of the Presidency of the Seventy. At their final meeting, Lazar presented Bateman with a tempered glass mosaic she had created, inscribed with this line from an Emma Lou Thayne poem: “The pillars of my faith are still intact but the roof has blown blessedly off the structure to reveal a whole sky full of stars.”

About a year ago, Lazar and others formed another Mormon/non-Mormon dialogue group, this time made up of men and women, who meet once a month. The group has become close, she says; one member recently introduced the group to his fiancee and invited everyone to his upcoming wedding reception.

Lazar’s hope is that lots of Utahns will form such groups, and when she speaks next summer at Women’s Week at BYU, she’ll make that suggestion. And she’ll talk about the basics: listen, be respectful, don’t come in with an agenda, “talk because you want to understand. … It’s like pure research,” she says, “not knowing where it’s going to take you.”

Local, grassroots efforts like these can often spread beyond the borders of a neighborhood, a city or a state.

And President Hinckley’s words from October 2003 could serve as the foundation of a playbook for interfaith efforts anywhere: “We cannot be arrogant. We cannot be self-righteous. The very situation in which the Lord has placed us requires that we be humble as the beneficiaries of His direction. “While we cannot agree with others on certain matters, we must never be disagreeable. We must be friendly, so-spoken, neighborly and understanding.”

Faith leaders praise late Mormon leader Monson’s charity — Sermon on the Mount was his ‘way of life’, by Bob Mims, Salt Lake Tribune, January 5, 2018

Faith leaders joined Wednesday in praising the late LDS Church President Thomas S. Monson for his ecumenical outreach, charitable impulses at home and abroad, and for offering a ready hand of friendship across ethnic, national and religious divides.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops stated that Monson, who died in Salt Lake City late Tuesday at age 90, was “known for his hands-on approach and concern for the poor,” even as he “presided over a church confronting challenges and change, within and without.”

Cardinal Daniel N. DiNardo, president of the Washington, D.C.-based group, remarked that Monson’s tenure as president of the Utah-based Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was highlighted by “understanding and friendship . . . between our two communities on national and local levels [concerning] important questions on family and the dignity of the human person.”

“Catholics and Mormons work together and support each other,” DiNardo said. “Today, Catholics join their Latter-day Saint brothers and sisters in commending his soul to the mercy and love of God.”

In Utah, the Rev. Oscar A. Solis, bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Salt Lake City, saluted Monson as a leader who “joyfully served his church and the broader community selflessly and humbly for many years.”

“[He] has been a good friend and supporter in our mutual efforts to support the common good and care for the most vulnerable both at home and abroad,” Solis added. “ … For President Monson, the Sermon on the Mount was not just a platitude but a way of life.”

The bishop concluded by recalling Monson’s ability to see “the image of Jesus” in people, regardless of their faith traditions. “His was a ‘human’ touch of kindness and dignity that will long be treasured.”

The Rev. Scott B. Hayashi, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Utah, admired Monson’s kindness, delivered with “a calming voice” whether individually or before a broadcast audience of millions of Mormons.

“I will always appreciate the LDS Church’s generous dedication to interfaith ministries under his presidency,” Hayashi said, “and throughout his many years of devoted service.”

Greg Johnson, director of Utah’s Standing Together, an organization dedicated to Mormon-evangelical Christian dialogue that stood against so-called “street preachers” who harangued LDS General Conference attendees in the past, also mourned Monson’s death.

“We in the local evangelical community offer our compassion and regard for the LDS community in relation to this very significant and emotional time for the LDS people,” he said.

Leaders of Utah’s Jewish community offered their condolences as well.

Rabbi Ilana Schwartzman, who is leaving Utah after overseeing Congregation Kol Ami for seven years, counted Salt Lake City’s Jews as “blessed to have had a strong relationship with President Monson.” She added that she “appreciated all that he did with and for our community [as an] advocate for interfaith conversation and cooperation.”

Added Rabbi Benny Zippel of Chabad Lubavitch of Utah: “President Monson was a deeply godly individual. I was very moved by his humility, kind spirit and his deep commitment to upholding God’s values in this world.”

Zippel especially treasured the memory of standing “together [with Monson] on the steps of the state Capitol in January 2009. … It was a very cold day physically, around 13 degrees, but his warmth exuded in a very clear fashion, nonetheless.”

Salman Masud, president of the Islamic Society of Greater Salt Lake, said Muslims admired Monson “for his kind nature and service. Aging is not necessarily essential for greatness, but living effectively is.

“We will remember him as a compassionate leader whose charitable nature benefited the needy locally and victims of disaster across the world,” Masud added. “During his tenure, Muslims always felt Utah to be a warm and welcoming home.”

Sympathy also came from Rajan Zed, a Hindu cleric and leader of the Reno, Nev.based Universal Society of Hindus.

“[He was] a great humanitarian who collaborated with other religions . . . worldwide on programs aimed at improving the human condition,” stated Zed, also describing Monson as “an affable, kind and approachable leader” who expanded the LDS Church’s international relief efforts.

First Presidency and NAACP Leaders Call for Greater Civility, Racial Harmony, Newsroom, 17 May 2018

The First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the national leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) are calling for greater civility and racial harmony. Senior Church leaders and the NAACP released a joint statement Thursday morning following a meeting in the Church Administration Building on Temple Square in Salt Lake City.

“Today, in unity with such capable and impressive leaders as the national officials of the NAACP, we are impressed to call on people of this nation and, indeed, the entire world to demonstrate greater civility, racial and ethnic harmony and mutual respect,” said President Russell M. Nelson, who was joined by his counselors, President Dallin H. Oaks and President Henry B. Eyring.

“The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints continues to affirm its fundamental doctrine — and our heartfelt conviction — that all people are God’s precious children and therefore our brothers and sisters,” said President Nelson.

“We compliment The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for its good faith efforts to bless not only its members, but people throughout the United States and, indeed, the world in so many ways,” said Derrick Johnson, president and CEO of the NAACP. “These include humanitarian and welfare services, pioneering work in higher education and promoting the dignity of all people as children of God.”

In addition to Johnson, other NAACP leadership in attendance at the meeting included Leon W. Russell, chairman, board of directors; Wilbur O. Colom, special counsel to the board of directors; Jeanetta Williams, local Utah branch president; and Dr. Amos C. Brown, chairman of interfaith relations.

The NAACP and Church leaders are exploring a possible service project where local members of each organization can work together, as the Church does with a number of organizations. Current plans are being considered to increase education and wage improvement among members of a mutually identified community.

“The thing that’s great about this morning is that we’ve begun a dialogue, a dialogue I think that will be fruitful in the sense that it gives us an opportunity as two organizations that believe highly in education, that believe there’s a need to eliminate poverty in this world and eliminate hunger in this world,” said Leon W. Russell, chairman of the NAACP board of directors.

“I’m thoroughly impressed that this program and this news media opportunity came together,” said Donald Harwell, a Latter-day Saint in Utah.

“I look forward to wonderful, marvelous things happening because of this joint venture. And I applaud it. I thank God for it,” said Catherine Stokes, a member of the Church.

On Friday, Church leaders hosted a luncheon for the NAACP and invited community members. Paul Cobb, a lifelong NAACP member and a newspaper owner in Oakland, spoke of his decades-long friendship with the Church. When he was editor of the Oakland Tribune some 25 years ago, he was approached by a Church leader who asked him to write articles about Latter-day Saints.

“Little did I know, after 21 articles and being inspired by what I discovered about the Church, I found out that prophet [Gordon B.] Hinckley of the Church had made copies of those articles and circulated them to all the members of the apostles. And it was required reading,” Cobb said. “When I finally met the apostles and I met the prophet, they all knew who I was, and I didn’t know why or how they had known.”

Pointing to the JustServe pin on his jacket, Cobb said Thursday’s announcement embodies the idea that the NAACP and the Church “are here to move forward into the rest of the 21st century with the motto of ‘Let’s Just Serve.’” He also said he hopes this partnership “will cause us to rediscover the common bond of our rootage so that we can branch out to reach out to the rest of the country.”

On Sunday, the group will attend a special performance of “Music and the Spoken Word,” featuring the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra at Temple Square.

The NAACP’s visit to Salt Lake City comes two weeks before the Church’s 40th anniversary celebration of the 1978 revelation on the priesthood, scheduled for June 1 at the Conference Center.

Read the full statements below:

President Nelson

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints continues to affirm its fundamental doctrine—and our heartfelt conviction—that all people are God’s precious children and therefore our brothers and sisters. Nearly a quarter century ago, the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles proclaimed that “All human beings—male and female—are created in the image of God. Each is a beloved spirit son or daughter of heavenly parents, and, as such, each has a divine nature and destiny.”

Today, in unity with such capable and impressive leaders as the national officials of the NAACP, we are impressed to call on people of this nation and, indeed, the entire world to demonstrate greater civility, racial and ethnic harmony and mutual respect. In meetings this morning, we have begun to explore ways—such as education and humanitarian service—in which our respective members and others can serve and move forward together, lifting our brothers and sisters who need our help, just as the Savior, Jesus Christ, would do. These are His words: “I say unto you, be one; and if ye are not one ye are not mine” (Doctrine and Covenants 38:27).

Together we invite all people, organizations and governmental units to work with greater civility, eliminating prejudice of all kinds and focusing more on the many areas and interests that we all have in common. As we lead our people to work cooperatively, we will all achieve the respect, regard and blessings that God seeks for all of His children. Thank you very much.

Derrick Johnson

President Nelson, the statement you just made expresses the very core of our beliefs and mission at the NAACP. We admire and share your optimism that all peoples can work together in harmony and should collaborate more on areas of common interest. Thank you.

To the media, as the NAACP celebrates this 64th anniversary of the landmark decision Brown vs. Board of Education, like the Latter-day Saints, we believe all people, organizations and government representatives should come together to work to secure peace and happiness for all God’s children. Unitedly, we call on all people to work in greater harmony, civility and respect for the beliefs of others to achieve this supreme and universal goal.

We compliment The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for its good faith efforts to bless not only its members, but people throughout the United States and, indeed, the world in so many ways. The NAACP, through our mission, we are clear that it is our job to speak for those who cannot speak for themselves. And we do so in an advocacy voice, but now with a partner who seeks to pursue harmony and civility within our community. I am proud to stand here today to open up a dialog to seek ways of common interest to work towards a higher purpose. This is a great opportunity. Thank you for this moment.

Our Fading Civility, By President Gordon B. Hinckley, BYU Commencement & Inauguration Ceremony April 25, 1996

In your studies many of you have chronicled the march of civilization. It has been a truly remarkable odyssey as through the centuries society has made progress as people have lived together in communities with respect and concern one for another. This is the hallmark of civilization. And yet at times we wonder how much progress we have really made. This century which now draws to a close has witnessed more wars and more death and suffering than any other century in human history. Even today we witness the tragedies occurring in Liberia, in Israel and its neighbors, in Bosnia, in Ireland, and everywhere. Civility and mutual respect seem to have disappeared as people kill one another over ethnic differences.

But civility also appears to be fading much closer to home. Civility covers a host of matters in the relationships among human beings. Its presence is described in such terms as “good manners” and “good breeding.” But everywhere about us we see the opposite. This is evident in growing gangs, whose members show little respect for life and no respect for their enemies, who mar beautiful walls and buildings with their ugly graffiti, who evidently think only in terms of self. Crime is essentially an absence of civility.

A study sponsored by the National Institute of Justice, the research arm of the Justice Department, concludes that crime costs Americans at least $450 billion a year. Some question the methodology of the study, but surely no one can question the gravity of the problem. An article on this subject points out that another $40 billion could be added, bringing the total annual cost of crime to almost $500 billion. No one can comprehend a figure of that magnitude. But it is interesting to note that the Defense Department’s budget for last year was $252.6 billion, which means that the cost of crime is essentially twice what we spend for the defense of this nation and in giving military assistance to other nations. It is appalling. It is alarming. And when all is said and done the cost can be attributed almost entirely to human greed, to uncontrolled passion, to a total disregard for the rights of others. In other words to a lack of civility.

As one writer has said, “People might think of a civilized community as one in which there is a refined culture. Not necessarily; first and foremost it is one in which the mass of people subdue their selfish instincts in favor of the common well being” (Royal Bank Letter, May-June 1995). He continues: “In recent years the media have raised boorishness to an art form. The hip heroes of movies today deliver gratuitous put downs to ridicule and belittle anyone who gets in their way. Bad manners, apparently, make a saleable commodity. Television situation comedies wallow in vulgarity, stand up comedians base their acts on insults to their audiences, and talk show hosts become rich and famous by snarling at callers and heckling guests.” (Ibid)

All of this speaks of anything but refinement. It speaks of anything but courtesy. It speaks of anything but civility. Rather, it speaks of crudeness and rudeness, and an utter insensitivity to the feelings and rights of others. It is so with much of the language of the day. In schools and in the workplace there is so much of sleazy, evil, filthy language. I hope that every one of you will rise above it. You are now graduates of this great institution. You cannot afford the image of those whose vocabularies are so impoverished that they must reach into the gutter for words with which to express themselves. Along with such uncouth talk is so much of profanity. It too marks a lack of civility.

The finger of the Lord wrote on the tablets of stone, “Thou shalt not take the name of the LORD thy God in vain; for the LORD will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain.” (Ex. 20:7) Sloppy language and sloppy ways go together. I hope that you have learned more than the sciences, the humanities, law, engineering and the arts, while you have been here. I hope that you will carry with you from this hallowed place a certain polish that will mark you as one in love with the better qualities of life, the culture which adds luster to the mundane world of which we are a part, a patina which puts a quiet glow on what otherwise might be base metal. Said the Savior to the multitude: “Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men.” (Matt. 5:13)

Civility is what gives savor to our lives. It is the salt that speaks of good taste, good manners, good breeding. It becomes an expression of the Golden Rule: “Therefore, all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.” (Matthew 7:12) My dear young friends, you of the graduating class of 1996, as I compliment you on your achievements, may I add that these will not count for much unless they are accompanied by marks of gentility, of respect for others, of going the second mile, of serving as the Good Samaritan, of being men and women who look beyond your own selfish interests to the good of others. Only as you do so will you find fulfillment.

It is an interesting world that lies ahead. In some respects it is a jungle. It is the absence of civility which creates the jungle. No matter the extent of your education. No matter the degrees which you may add to those you receive today. No matter your achievements in science, business, the professions, or whatever. If that other dimension of which I have spoken is missing, you will have lost that which is most precious, that is, the Godly quality of reaching out with respect and kindness, with courtesy and appreciation to help others. We are approaching political campaigns, during which we will hear much talk. We should bear in mind that shouting, defaming, boorish and crude talk and greedy acts only destroy the refining elements of life. As scripture reminds us, it is the soft answer that turneth away wrath. (See Prov. 15:1.)

I plead with you as you now go your separate ways, to take with you not only your diplomas, not only the transcript of your credits, but the mark of refinement that you should have cultivated while here in this institution. I am not suggesting that you be soft and docile. I hope you will be enthusiastic and aggressive as you pursue your objectives. But I also hope that you will also be enthusiastic and aggressive as you reach out to lift, to help, to encourage those whose lives you can touch for good. God bless you, my beloved friends, that as you walk the high road of life you will savor the sweetness of service, molding your influence, bringing your powers of persuasion, bringing your simple, quiet, everyday actions as an antidote to the fading civility of our society. If you do so the world will be so much the better for your presence and you will be so much the richer in your living. To this end I pray for your happiness as well as for your success, as I leave my blessing upon you, in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

The Montagu Principle: Incivility decreases politicians’ public approval, even with their political base, by JA Frimer and LJ Skitka, in J Pers Soc Psychol. 2018 Nov;115(5):845-866. (Abstract)

- W. Montagu asserted that, “civility costs nothing and buys everything.” In the realm of social judgment, the notion that people generally evaluate civil people more favorably than uncivil people may be unsurprising. However, the Montagu Principle may not apply in a hyper-partisan political environment in which politicians “throw red meat to their base” by unleashing uncivil, personal attacks against their opponents, satisfying the aggressive desires of their most hyper-partisan supporters, and thus potentially redoubling their approval among them. We conducted 2 longitudinal/observational studies of U.S. Congress and President Trump, and 4 experiments (N = 4,837) involving real exchanges between President Trump and his adversaries and a speech by a fictitious politician. Civility helped or did not affect-but never harmed-the reputation of the speaker, supporting the Montagu Principle. Even self-identified “diehard supporters” of President Trump, for example, evaluated the president more favorably after he responded with civility to a personal attack. Uncivil remarks uniquely diminished the speaker’s reputation, and had little impact on the reputation of the targets of the attack, the perceived winner of the verbal exchange, the reputation of the speaker’s party, or the sense that the country is moving in the right direction. Incivility made the speaker seem less warm and did less to affect perceptions of dominance or honesty. This warmth deficit explained the reputational costs of incivility. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2018 APA, all rights reserved).

Complimenti ottima recensione. Grazie da archglob.com

Bellissimo articolo, un grazie da archglob.com